Fil-Am honored with prominent feature at Washington war memorial

A Filipino-American US Army soldier, who narrowly escaped death after he was shot through the pelvis by a sniper in Iraq and endured a grueling rehab to get out of his wheelchair, has become one of the new faces of American war veterans with his photo prominently featured at the newly-unveiled American Veterans Disabled for Life Memorial in Washington, D.C.

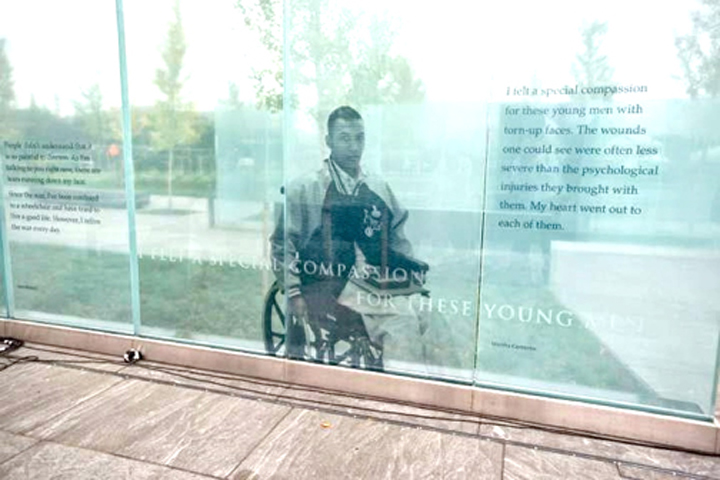

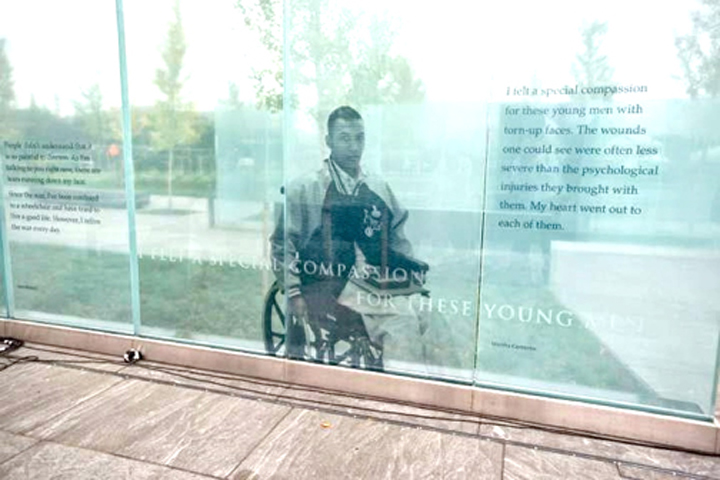

Joseph “Joe” Bacani, 29, currently a junior psychology major at Columbia University, said he was both shocked and humbled upon learning only a week prior his place of honor on the wounded-vets memorial which shows him still in his wheelchair after being awarded the Purple Heart.

Joseph “Joe” Bacani, 29, currently a junior psychology major at Columbia University, said he was both shocked and humbled upon learning only a week prior his place of honor on the wounded-vets memorial which shows him still in his wheelchair after being awarded the Purple Heart.

“I thought my image would be small, with thousands of veterans alongside me,” said Bacani at the recent unveiling of the memorial, with his image and story next to Bob Dole’s, the late senator who was severely wounded in World War II.

“Then I saw the image, and I was like, ‘What? Are you kidding me?’ I’m larger than life-sized on that wall!”

Bacani, who grew up in Tustin, California and joined the Army at 17 when he was still in high school, said he has always seen himself “as just like a normal average Joe.”

The memorial, which took 16 years to complete and was funded by $80 million in private donations, sits within view of the Capitol.

It’s a collection of glass and granite walls representing wounded veterans from all wars and branches — of whom an estimated three million are alive today — clustered around an eternal flame.

“It doesn’t end with the war; they live with it forever,” said Project director Barry Owenby.

“They have a trauma of injury, a healing process, and then their rediscovery of purpose. So that’s the story that we’re trying to tell here.”

Bacani, who was inspired to join the Army after 9/11, was deployed to Iraq in November 2006 and was stationed at Camp Liberty in Baghdad.

From the beginning, he had a bad feeling, he recalled in an interview the New York Post.

“We deployed with maybe 20 scouts and six snipers,” said Bacani, who was a cavalry scout assigned to the 1st Cavalry Regiment from Fort Hood, Texas.

“I was really conscious about how shallow our platoon was.”

“I was really conscious about how shallow our platoon was.”

On March 20, 2007, Bacani and his platoon were doing route clearance, sweeping for IEDs, or improvised explosive devices.

“It was just five guys on foot and three or four other trucks full of guys,” he said.

Bacani, in 50 pounds of body armor, had the mine sweeper.

“So we found the IED,” he shared, “and five minutes after that, I first heard the clack from a rifle. And I was just like, ‘Oh, God. I know what that sound means.’”

Bacani didn’t even have time to look back at his friend, Spc. Jesus Bustamante, who was also on foot.

“I was trying to find out where the sniper was shooting from,” he said.

“And as soon as I figured it out, I got shot.”

He was shot in the tailbone and the bullet came out of his pelvis “as if the strongest person on the planet really hates your guts, and he got this sledgehammer from a blacksmith oven and took all his might and whacked you right on your ass,” he confided.

Bacani tried to take cover, but he collapsed on the open road, all sense in his right leg gone.

He was an open target.

“I was just lying there, feeling this 140-degree sun, in full battle rattle,” he remembered.

“And I was just like, ‘I guess this is where I may die.’”

After playing dead, he cursed at the top of his lungs so his sergeant would know he was still alive.

Bustamante had been shot twice — once in the knee and once in the rib, the bullet tearing through most of his vital organs and leaving him near death.

Still, Bustamante “had this grenade launcher, the M203, and he fired rounds into the building. I think he saved both of us that day,” Bacani pointed out.

Bacani thought they were on the ground for 30 minutes — “a reasonable time” — before they were rescued and loaded into a Humvee and eventually flown to the Green Zone for emergency surgery.

Unable to walk, Bacani was flown to Walter Reed, where he underwent intense rehab.

It took him six months to walk without assistance, and still he wanted to go back to Iraq.

He thought constantly of the many friends he had lost while serving there.

In fact, two months before Bacani was shot, he had lost his roommate and best friend, Pfc. Darrell W. Shipp, who had become an older brother to him.

On April 6, 2007, Bacani received The Purple Heart, awarded to US servicemembers wounded by an instrument of war in the hands of the enemy; it is one of the most recognized and respected military decorations.

He also received the Combat Action Badge, which is awarded for actively engaging, or being engaged by, enemy forces.

On hand to see him receive his decorations were his Ilocos Sur-born parents Norberto and Rosita, and his sister Jackie.

“I can’t tell you how much it means to me that he has come home,” Jackie said in a past interview. “He’s one of the lucky ones.”

Jacquie said that during Bacani’s deployment, she and her parents got on their knees and prayed for her brother’s safety every night.

“I know that not a lot of people are able to come home, and I’m just so grateful,” Jackie said.

Today, Bacani still suffers from “intermittent and shocking nerve pain” that lasts about two minutes, according to the Post.

He has aching muscle pain every day and expects to have it for the rest of his life.

He wears three KIA memorial bracelets — one each for his closest friends who perished in Iraq.

“This is not everybody I’ve lost,” he said.

On each of their birthdays, he said to himself: “I’m living your life. I’ll take over from here.”

On Aug. 18, he enrolled at Columbia University, which has a long history of recruiting veterans and providing financial aid.

This past May, 145 veterans graduated from the university.

“I’m so happy I’m here,” Bacani said. “I wouldn’t have been able to live with myself if I just went to community college.”

He finds it ironic to now be in New York, “because after I got out of the Army, I just wanted peace and quiet,” he says.

“But moving to New York — I feel like I’m reborn. I have all these opportunities in front of me.”

He’s majoring in psychology and plans to go into PTSD treatment and research.

He still feels guilty he’s here and not in Iraq.

“People are always telling me that I did enough, that I don’t have to go back,” he said.

He’s proud of this new memorial and his place in it, but he worries that people might see it and feel something, then go on about their lives without realizing how much help veterans need.

When asked if he thought his picture at the memorial was a window to his soul, Bacani said, “I hope so and I hope people can see beyond the wheelchair that there’s still a young man in there with many more years left to live, to make something out of himself.” —Filipino Reporter

Joseph Bacani's photo is prominently featured at the newly-unveiled American Veterans Disabled for Life Memorial in Washington, D.C. Filipino Reporter photo

“I thought my image would be small, with thousands of veterans alongside me,” said Bacani at the recent unveiling of the memorial, with his image and story next to Bob Dole’s, the late senator who was severely wounded in World War II.

“Then I saw the image, and I was like, ‘What? Are you kidding me?’ I’m larger than life-sized on that wall!”

Bacani, who grew up in Tustin, California and joined the Army at 17 when he was still in high school, said he has always seen himself “as just like a normal average Joe.”

The memorial, which took 16 years to complete and was funded by $80 million in private donations, sits within view of the Capitol.

It’s a collection of glass and granite walls representing wounded veterans from all wars and branches — of whom an estimated three million are alive today — clustered around an eternal flame.

“It doesn’t end with the war; they live with it forever,” said Project director Barry Owenby.

“They have a trauma of injury, a healing process, and then their rediscovery of purpose. So that’s the story that we’re trying to tell here.”

Bacani, who was inspired to join the Army after 9/11, was deployed to Iraq in November 2006 and was stationed at Camp Liberty in Baghdad.

From the beginning, he had a bad feeling, he recalled in an interview the New York Post.

“We deployed with maybe 20 scouts and six snipers,” said Bacani, who was a cavalry scout assigned to the 1st Cavalry Regiment from Fort Hood, Texas.

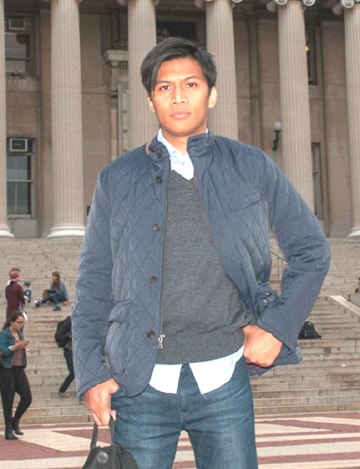

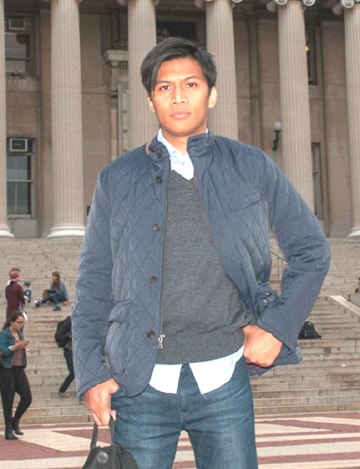

Joseph Bacani shown outside his school at Columbia University in New York City. Filipino Reporter photo

On March 20, 2007, Bacani and his platoon were doing route clearance, sweeping for IEDs, or improvised explosive devices.

“It was just five guys on foot and three or four other trucks full of guys,” he said.

Bacani, in 50 pounds of body armor, had the mine sweeper.

“So we found the IED,” he shared, “and five minutes after that, I first heard the clack from a rifle. And I was just like, ‘Oh, God. I know what that sound means.’”

Bacani didn’t even have time to look back at his friend, Spc. Jesus Bustamante, who was also on foot.

“I was trying to find out where the sniper was shooting from,” he said.

“And as soon as I figured it out, I got shot.”

He was shot in the tailbone and the bullet came out of his pelvis “as if the strongest person on the planet really hates your guts, and he got this sledgehammer from a blacksmith oven and took all his might and whacked you right on your ass,” he confided.

Bacani tried to take cover, but he collapsed on the open road, all sense in his right leg gone.

He was an open target.

“I was just lying there, feeling this 140-degree sun, in full battle rattle,” he remembered.

“And I was just like, ‘I guess this is where I may die.’”

After playing dead, he cursed at the top of his lungs so his sergeant would know he was still alive.

Bustamante had been shot twice — once in the knee and once in the rib, the bullet tearing through most of his vital organs and leaving him near death.

Still, Bustamante “had this grenade launcher, the M203, and he fired rounds into the building. I think he saved both of us that day,” Bacani pointed out.

Bacani thought they were on the ground for 30 minutes — “a reasonable time” — before they were rescued and loaded into a Humvee and eventually flown to the Green Zone for emergency surgery.

Unable to walk, Bacani was flown to Walter Reed, where he underwent intense rehab.

It took him six months to walk without assistance, and still he wanted to go back to Iraq.

He thought constantly of the many friends he had lost while serving there.

In fact, two months before Bacani was shot, he had lost his roommate and best friend, Pfc. Darrell W. Shipp, who had become an older brother to him.

On April 6, 2007, Bacani received The Purple Heart, awarded to US servicemembers wounded by an instrument of war in the hands of the enemy; it is one of the most recognized and respected military decorations.

He also received the Combat Action Badge, which is awarded for actively engaging, or being engaged by, enemy forces.

On hand to see him receive his decorations were his Ilocos Sur-born parents Norberto and Rosita, and his sister Jackie.

“I can’t tell you how much it means to me that he has come home,” Jackie said in a past interview. “He’s one of the lucky ones.”

Jacquie said that during Bacani’s deployment, she and her parents got on their knees and prayed for her brother’s safety every night.

“I know that not a lot of people are able to come home, and I’m just so grateful,” Jackie said.

Today, Bacani still suffers from “intermittent and shocking nerve pain” that lasts about two minutes, according to the Post.

He has aching muscle pain every day and expects to have it for the rest of his life.

He wears three KIA memorial bracelets — one each for his closest friends who perished in Iraq.

“This is not everybody I’ve lost,” he said.

On each of their birthdays, he said to himself: “I’m living your life. I’ll take over from here.”

On Aug. 18, he enrolled at Columbia University, which has a long history of recruiting veterans and providing financial aid.

This past May, 145 veterans graduated from the university.

“I’m so happy I’m here,” Bacani said. “I wouldn’t have been able to live with myself if I just went to community college.”

He finds it ironic to now be in New York, “because after I got out of the Army, I just wanted peace and quiet,” he says.

“But moving to New York — I feel like I’m reborn. I have all these opportunities in front of me.”

He’s majoring in psychology and plans to go into PTSD treatment and research.

He still feels guilty he’s here and not in Iraq.

“People are always telling me that I did enough, that I don’t have to go back,” he said.

He’s proud of this new memorial and his place in it, but he worries that people might see it and feel something, then go on about their lives without realizing how much help veterans need.

When asked if he thought his picture at the memorial was a window to his soul, Bacani said, “I hope so and I hope people can see beyond the wheelchair that there’s still a young man in there with many more years left to live, to make something out of himself.” —Filipino Reporter

Comments